The Pattern in the Sister Queens' Skirts

Jayarājadevī and Indradevī. Jayavarman VII’s “Sister Queens”. Well educated. Compassionate. And smart. At Angkor we see so many bas relief of the king and these two women sitting together - even on the five gateways into the royal city - that it is believed by many that they worked together to establish an infrastructure at Angkor, eight hundred years ago.

The best likenesses of these women are in the Preah Khan temple. The older sister, Indradevī, has been portrayed as the river goddess Ganga, and is standing under the roof of a palace. Her face looks like images we see of her in bas relief at other temples. Jayarājadevī’s face looks like the face we see on free-standing sculptures of her. Both women are wearing all the accoutrements of a queen. And they’re worshipped by locals as Jayarājadevī and Indradevī.

But Western scholars do not acknowledge that these two bas relief are Jayavarman VII’s sister queens – there is no inscription that identifies them as such. One world-renowned scholar told me they are simply “door guards”.

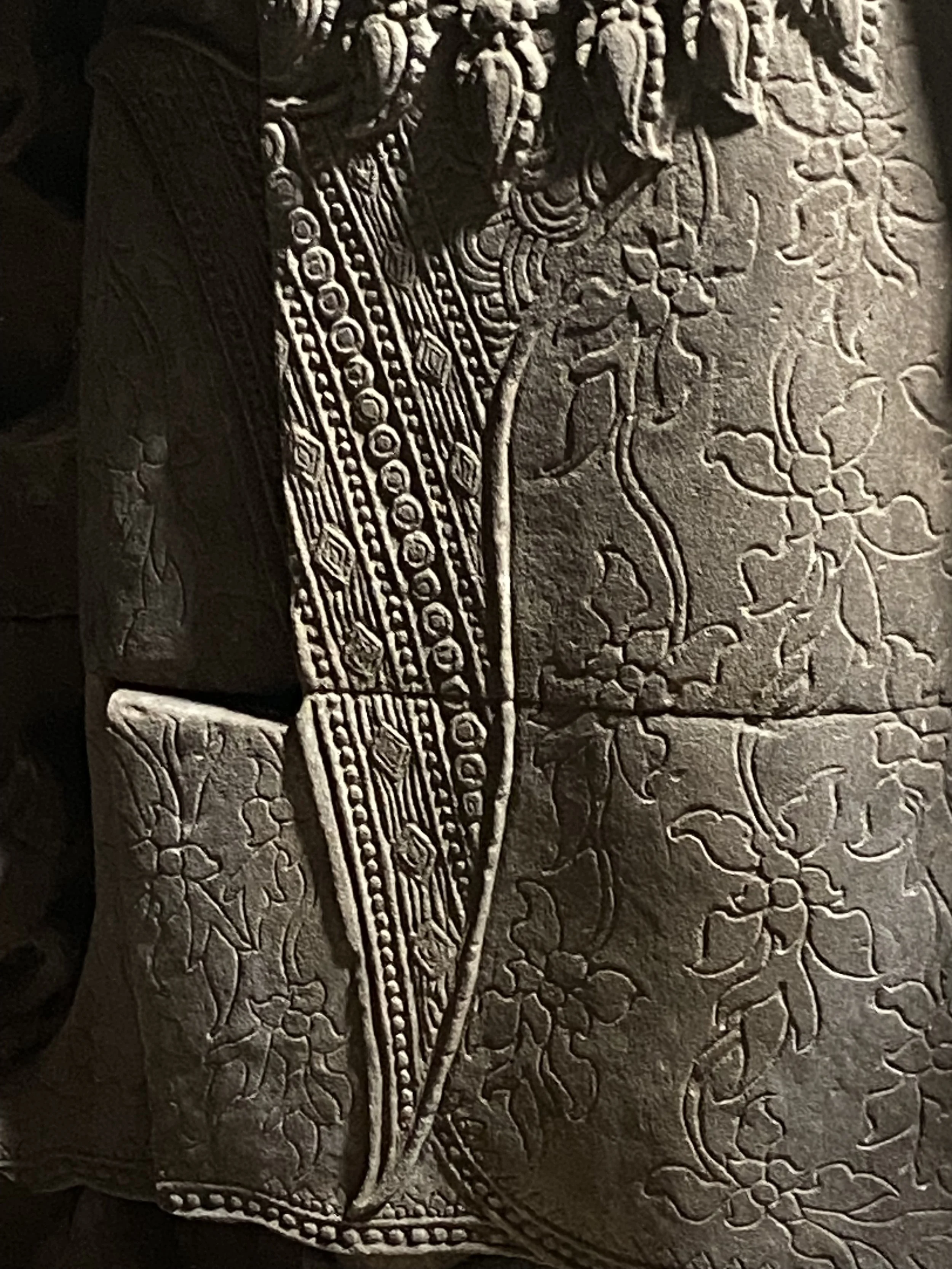

These scholars didn’t look at what the women were wearing. The pattern in their skirts (under their sashes) is so much alike that I believe the skirts were cut from the same piece of cloth - a common practice among sisters in Cambodia today. I knew it must have been imported silk. And if I could prove it, this would add to the evidence that these two images are, in fact, Jayarājadevī (below) and her sister.

Could I identify the pattern in the skirts? In 2023 I looked at a photo of every flower found in Cambodia today - all 525 of them. There was only one candidate. I got a match on the number of petals, and on the shape of the petals and the center of the flower. Then I looked at the stem - a match as well. The pattern in the queens’ skirts must be the Royal Poinciana flower, native only to Madagascar. But what clinched my identification was that the flower on the queens’ skirts was rendered to scale. Royal Poinciana are unusually large – today, as much as six inches across.

Next, I determined that it is highly unlikely that the Angkorians had the Royal Poinciana tree at the time the two bas relief were carved – so it wouldn’t be a Cambodian pattern. But, where was it from?

In 2024 I consulted textile experts from around the globe. They told me that the pattern was not Madagascaran, Indian, Chinese, Thai, Javanese or Malayan.

Then, with a research grant from the Victoria and Albert Museum, Karun Thakar Fund, I found the Royal Poinciana pattern in India. In Rajasthan - but I think the piece was made in Gujarat.

But, is this really the same pattern? Or a contemporary one, that just looks like it? This textile was certainly commercially produced, not hand made.

The most obvious similarity is in the scale. In the queens’ pattern and in this one, the flowers were rendered life-sized.

The next most obvious similarity is in the arrangement of the flowers. They’re in vertical rows. The rows are staggered; when you look at the pattern as a whole, the flowers zigzag across it. In Indradevī’s skirt we see a few much smaller flowers, of a different type, scattered in amongst the Royal Poinciana flowers; we see the same thing in the contemporary piece. I had originally thought that the pattern in each skirt was symmetrical, and that it was the fault of the sculptor that they didn't appear to be. But now, considering that Indradevī’s skirt contained a few small flowers and her sister’s didn’t, it is obvious that the pattern was not symmetrical.

Royal Poinciana come in red, red-orange, orange and yellow. Some have markings on them. We can see markings on the petals of the flowers in the textile above. The bas relief of the queens’ skirts would have been painted, and markings may have been painted in.

But there is one difference in the two patterns. In the queens’ skirts the flowers look like they’re connected, by flower stems with no leaves (the bottom of the stem of one flower touches the top of the flower below it). In the contemporary textile we see stems with leaves, and the stems don’t connect the flowers.

But, what was it that convinced me that the two patterns, eight centuries apart, are the same? In both patterns, there are the same number of Royal Poinciana per row. Five. In both patterns, the flowers are on the weft axis. And in both patterns, the rows are staggered.

And the sashes over the queens skirts? Ashavali brocade, from Gujarat. As is the strip of “fish eggs” at the bottom selvedge of each skirt. I found the Royal Poinciana pattern in a shop in Jaipur, but believe it also came from Gujarat. My research suggests that the Royal Poinciana tree went from Madagascar to Gujarat, and the pattern based on its flower was then developed in Gujarat. The full results of my investigation are in What the Queens Wore - the Silk of Angkor.

I think it only fitting that the sisters should be wearing Indian fabric. We know from the “Genealogy of the Kings of Cambodia” in George Coedes’ The Indianized States of Southeast Asia that they themselves were part Indian, through their maternal grandfather.

But was the Royal Poinciana pattern in the queens’ skirts rendered in brocade, ikat, or something else entirely? Here is how the experts weighed in.

Makara Lok (she is unique in that she makes both brocade and ikat) - “It would have been easier to make the pattern in ikat, but I think it was brocade.”

Archana Shastri - Brocade, block print, or painted fabric. Not ikat.

Rosemary Crill - Not ikat.

Lesley S. Pullen - Not ikat.

Paresh Patel - “Not an Ashavali brocade pattern. And asymmetrical? I would not try to weave such a piece - I don’t think it was brocade.”

Calico Museum, Ahmedabad - they did not reply to my inquiry

After I had consulted these experts, I realized that the question I had put to them was incomplete. We can not see the color of the pattern. So we don’t know if the flowers were filled with color (a different color than the background of the skirt) or if the pattern was only the silhouettes of the flowers. Pigment testing would be inconclusive, as discussed in my book. If the pattern was only the silhouettes of the flowers, it might have been embroidered.

OK, so what do we have? Because the pattern was not symmetrical, it is unlikely to be brocade or block print. 4 of the 5 experts said they thought it was not ikat. I am now leaning toward Archana Shastri’s conjecture that the fabric might have been painted. I will continue my research. If the piece I found in Jaipur had a label or stamp to identify the manufacturer, I could approach them to ask where they got the pattern. But it does not.